A multipitch adventure in Pulau Tioman

Nāga is a Sanskrit word for a mythical race of half-human, half-serpent divine beings. Found in various Asian religious and cultural traditions, they are often depicted as cobra snakes or dragons and routinely associated with bodies of water.

Alternatively, Indo-European etymology explains that the Sanskrit word nāga can also mean “cloud”, “mountain”, or “elephant.”

In Malay folklore, nāga refers to the form of Seri Gumum, a princess cursed to become the eponymous serpentine dragon creature who turned into the island of Tioman. Hence, legend has it that the distinctive and formidable granite towers found on Tioman are her horns.

Getting there

Even though Tioman is off the coast of neighbouring Malaysia, travelling there is not particularly convenient nor straightforward. When I was a child, there were direct flights from Singapore into Tioman Island, but Tioman Airport is permanently closed. Now, the commute goes something like this:

Woodlands Checkpoint → Cross the border to JB Sentral → Cab to Larkin Bus Terminal → 3h bus ride to Mersing Jetty → 2h ferry ride to Tioman Island

Aside: when I told my parents I was going on an impromptu (literally agreed to it the week before) climbing trip to Tioman and outlined this commute, he questioned why we would put so much effort into traveling to climb. His incredulity made me realise that I was accustomed to the logistical nightmare and physical toll of climbing trips. This comes from a combination of needing transport to enter into remote places and infrastructure not being catered specifically for travelers: i.e only made possible/easier if you were a local or lived near the rock face. In fact, I tried to point out to him that climbers often do far more for much less: professional big wall climbers conduct expeditions that are far, far more logistically challenging—requiring weeks of travel in various modes of transport and hauling food and equipment in extreme environments. 1

Furthermore, we stayed in a little village on the island called Mukut, which is a far cry from the touristy mainland resorts Tioman is known for. Another part of climbing trips we expect and get used to. So, to my readers who wonder how we make these trips happen—we tap on “fixers” who are really just local climbers/locals embedded in the climbing community that make arrangements for foreign climbers to smooth over things like accommodation, local transport and street directions.

I’m actually not sure why I decided to say yes to this trip. This multi pitch climb in Tioman has a rather sketchy reputation within the climbing community: we had heard (and upon doing our research before the trip, confirmed) that it was runout2, route finding was tricky and it was associated in our minds with several accidents—someone had broken something in their back from a fall on pitch 3 and others had gotten badly lost and needed to be rescued. But I followed this feeling that grew in me, this instinct that told me that whatever was going to happen on this adventure, it would leave an indelible mark on me and that I owed it to myself to see what would bloom from this.

Research and preparation

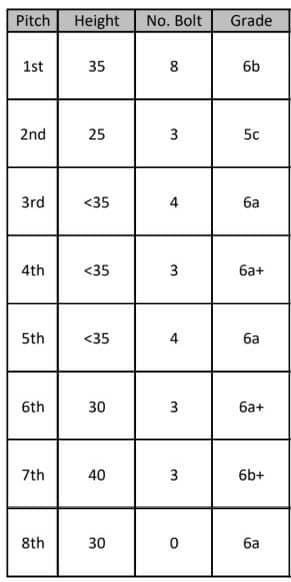

A lot of climbing trips is preparation. We read websites3 and blogs4 written by climbers who’ve done the same route, we check how long each pitch is (so we know what length of rope to bring) and how many bolts there are (to bring enough quickdraws and/or cams), what type of anchor system to expect (so we bring enough/the right slings and carabiners) and what the route is like. This is a mandatory step and—I emphasise—not optional. A lack of preparation means death or serious injury, in the best case scenario.

This newsletter is not just an adventure log but also, hopefully, a repository of resources for future climbers intending to do similar trips. In spite of all the preparation and precaution you take, there are plenty of unknowns still. You don’t know what the weather will be like on the day itself (raining means no climbing), you don’t know for sure what the route is like or how it would feel. The information you have could be outdated or plain wrong. So you take what you can get and you keep an open mind.

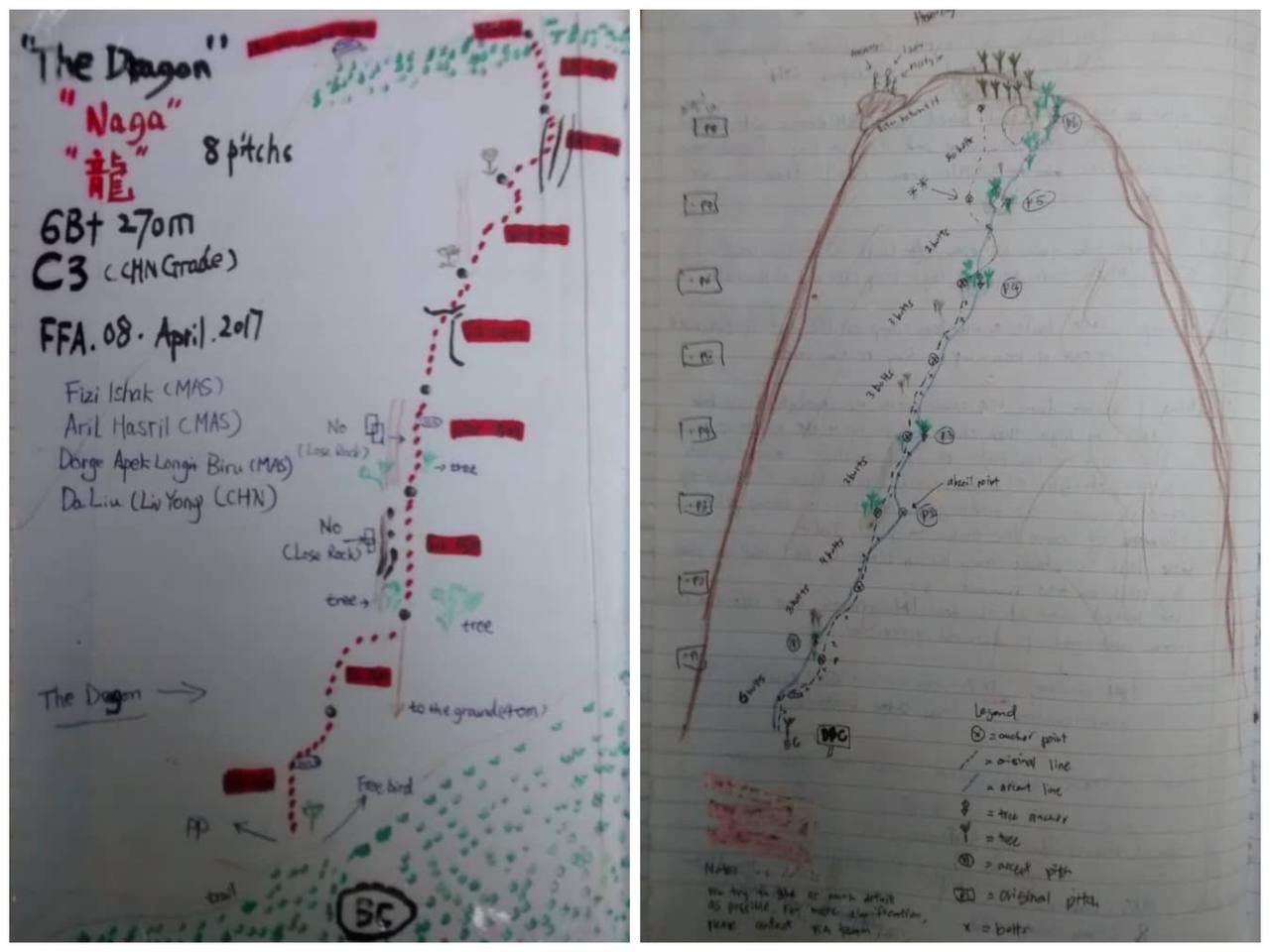

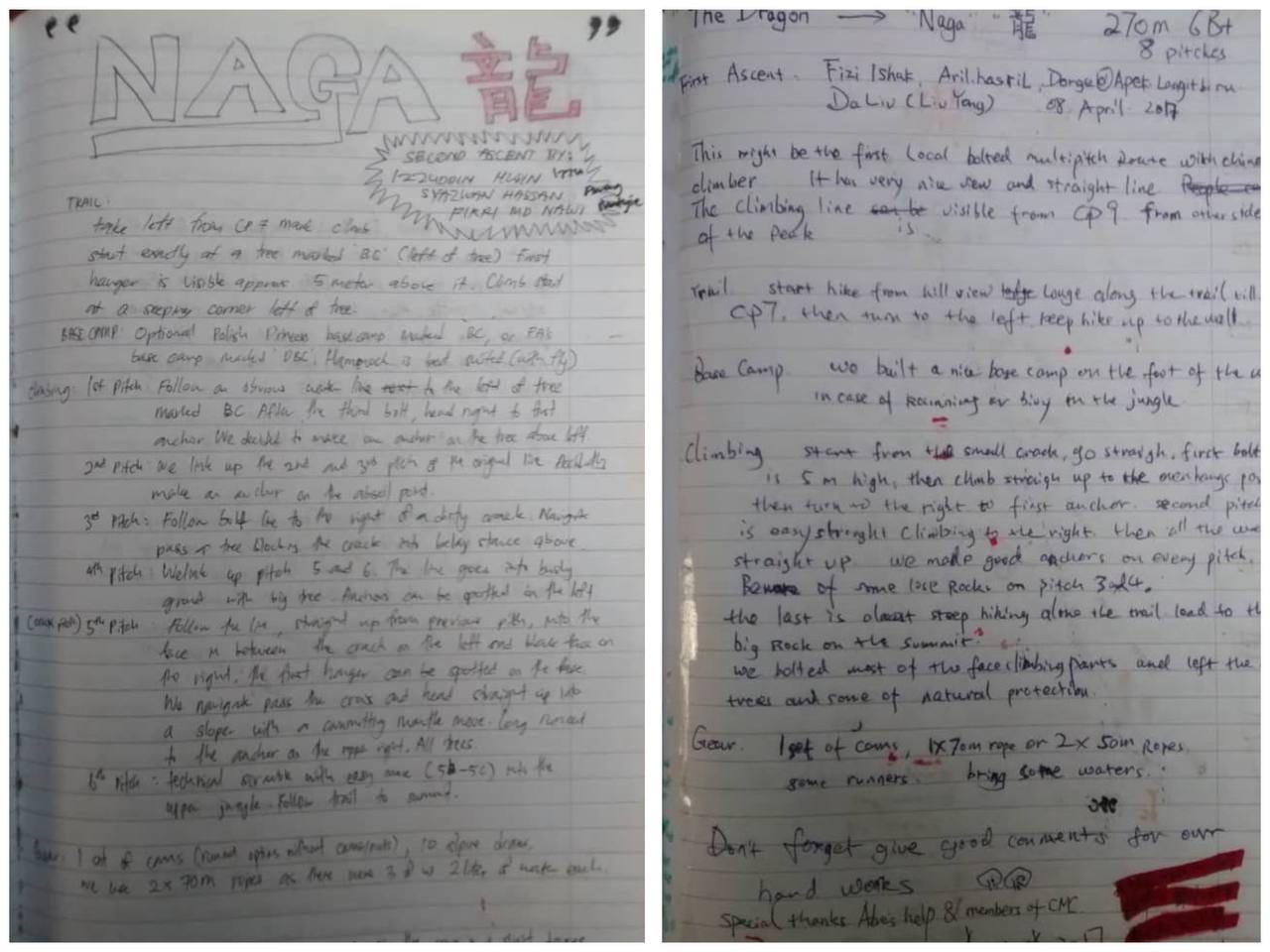

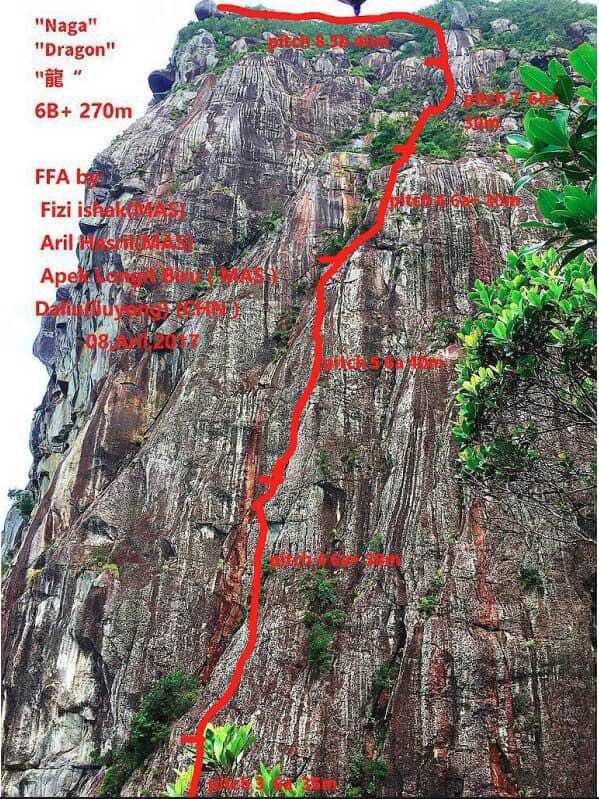

Here are some of the very informal topos we received from Pak Tam, the local climber who first established another more difficult multipitch named Damai Sentosa, together with “Uncle Sam.” I thought, how quaint. Generally, outdoor climbing is a burgeoning activity in Southeast Asia. Often, routes are established with the help of climbers that come from the West (typical or what?) and so things like route information remain rather informal, still. Hand drawn maps and topos are common, or knowledge is passed orally.

Of our small group of 4—we would climb in pairs—1 of us had climbed Naga recently and was therefore familiar with the route. We relied on his routefinding immensely. So, it also helps to go with someone who has experiential knowledge of the climb.

The first day

Woke up at 4am to take a cab to Woodlands Checkpoint. Starting in the dark seems to be the common thread in all my outdoor adventures. Luckily, I knew that we wouldn’t be doing anything except travelling to Tioman and packing for the climb on the first day, so a little bit of sleep deprivation was bearable.

Our little hut in Mukut was in a sleepy corner of the island overlooking the beach. There was only 1 real eatery here that was really just a little cafe on stilts overlooking the shore. With a hot and dry afternoon stretching ahead of us and nothing to do, we took a little dip in the sea after packing all our gear for the next day. The toilet had no shower head or hot water, just a tap that I filled up a bucket and boiled hot water in the electric kettle to mix with. After all, what’s the point of a fancy toilet if you’re spending all your time climbing?

We also met Pak Tam, whose dwelling sits by the entrance of the hike to Naga. climbers have to “register” their names and contact numbers on paper; just in case they don’t come back by nightfall and need rescuing. Access fees were negligible, and they go to Pak Tam. He hobbled over to us, an ankle injury acquired from falling on a route in his younger days and never set right. ‘Hospital too far away,” he rasped by way of explanation. He had a hangboard5 that he gestured to when he relayed his story of establishing this route, telling us how much he had trained and miming the way he would do pull ups on the hangboard. “Be careful,” he warned us, his swollen and twisted ankle our cautionary tale.

I couldn’t stop thinking about him, long after we’d left to go back to our hut. I pondered the passage of time, the promise and fragility of youth, eternity and mortality. I wondered what his life had been like since. Did he have a family who took care of him? None that I saw. What did loss of that sort feel like? Is he proud that his legacy would be establishing access to the South Tower, or was it a bittersweet reminder of a life of climbing cut short? It was beyond my ability to imagine accepting that kind of pain and suffering and inconvenience for years on end, and yet, indeed, this is not an uncommon story around rural villages everywhere, I am certain. I felt my lack of worldliness then.

We slept early that day at 7pm. Our plan was to begin the approach at 4am in the dark and hike for 2h in the jungle until we reached the start of the climb. A background hum of anxiety is my ever present companion the night before a big climb. It is my first waking thought in the morning shuffle to change, force down breakfast, check my bag and leave to meet my fate on the wall.

Approach

Headlamps are a staple on climbing trips. There’s always a chance you run into a problem and get stuck on the wall past sunset. And, for big climbs, you’d start as early as possible and so usually begin in the dark.

It’s hard to start so early in the morning and in the dark. It’s harder still to hike insistently uphill for 2h in the humid rainforest of the Tropics. Your sweat doesn’t evaporate and you’re sticky and questioning if you’ll have energy left when you haven’t even begun the climb. The path is well trodden but it was easy to miss the last checkpoint before the wall. Bashing through thorny bramble and thick foliage was just another one of those things you accept in your desire to reach it.

Pitches 1-6

When we finally began climbing dawn had just broken over the horizon. Climbing in pairs, our friends RZ (leader) and E (second) went first. We decided beforehand who would lead and follow. This multi pitch is not like Alpendurst in that it is sparsely bolted. We’re not sure why. Rumour has it that the bolters’ drill ran out of power during the first ascent of this climb and nobody bothered to go back and bolt the rest of the route. An alternative hypothesis suggests that bolters felt it was easy enough that falling was unlikely and so bolting was unnecessary.

From this chart, you can see that on the last pitch, it’s a 30m climb but there are ZERO bolts. I laughed when I first saw this. The topos show that the last pitch is basically just jungle climbing. More on that later below.

So to ensure that we weren’t doing 10m runouts, we had to do what is called “mixed trad” climbing. So the boys brought their trad rack to cover the sections that weren’t bolted. E and I aren’t trained nor confident in placing cams so we climbed as seconds. As Ryan climbed, my anxiety would increase proportional to how runout the pitch was, and only subside momentarily each time he managed to find a crack to place protection into.

The climbing was easy, but to my mind, the prospect of an accidental slip of a foot always remained a possibility. With the pitches so runout, my anxiety was mainly for Ryan who was leading, and not so much myself.

Granite

Interestingly, and in contrast to most of Southeast Asian climbing, the rock is granite and not limestone. Limestone tends to form tubular structures like tufas and features such as finger pockets. Often there are sharp and pitted areas (imagine what it looks like when acid falls downwards onto a vertical calcium carbonate structure). Granite surfaces look feature-less but the rock itself is high friction. The surface has small indentations but they are shallower and wider than the scarred surface of limestone. Instead, granite has large faultlines in the rock, which are cracks in between that we can place cams into for protection.

I rarely have the opportunity to climb on granite, so this was a pleasantly novel experience. I enjoyed the security of placing my feet and, knowing it wouldn’t slip, confidently making the next move. The face is slabby, so there’s less effort pulling with your arms and we rely more on pushing with our legs and feet.

Belaying

We all had 1 major gripe about this route (other than that it’s difficult to get to and runout): the anchor bolting is totally heinous. The bolts were in locations that were just a little bit too left/right/low/high for one to comfortably rest between pitches and to belay from. It was totally counterintuitive. WHY would anyone do this to themselves and others? It was insane. We grumbled incessantly about this as we moved from anchor to anchor.

I remember being at this anchor before pitch 2, secured with my safety lanyard, having to readjust my stance every 15 seconds to one that would give me but another only brief reprieve from my perpetually flexed calves burning with exertion trying to remain in a stable belaying position. The sun was unrelenting, too. In moments like this, I often ask myself, why am I doing this? I could be comfortable but instead I chose suffering. I don’t have an answer for you.

Overlapping ropes

There was another climbing duo behind us. A Russian father and his young son. I tend to get antsy and nervous when people are climbing behind us on a multipitch because there’s pressure to move faster and not hold up the anchor unnecessarily. We were lucky that no other climbers went before us, but the presence of this climbing pair messed with my headspace. At some point, the father must have felt we were taking longer than he was willing to wait for and began climbing past us, thus creating an alternative route. This meant he was running out the rope at dangerous levels and my anxiety spiked watching him. He was obviously an experienced climber and willing to take on more risk. I do not have a problem when people decide to take more personal risk, but I draw the line at the point where their behaviour is risking my or others’ safety. At one point during pitch 2 , he had clipped his rope through the same bolt as us and his quickdraw and rope were crossing over mine. I was incredibly annoyed because I saw that his child was climbing on top rope below me and felt put upon to make a decision about removing his equipment momentarily to retrieve mine. I also couldn’t be 100% sure he was belaying his child from an anchor and that element of uncertainty contributed to my decision agony. There was no severe risk that his child would be endangered by the removal, but I was pissed that his impatience was now inconveniencing my climb and contributing to my ratcheting anxiety level. The onus fell solely on me to rectify the overlap and that was so unfair. Complex decision making is a different beast when you’re hanging off with one hand a hundred meters above ground.

Features

During the act of climbing itself, the world narrows to your breath and the movements. You’re distantly aware that you’re scaling an incredibly tall rock face but that fact doesn’t really hit you until you look at the photos or you see the route you did from afar. But what never fails to rekindle my wonder at and connection to the natural world is when we stumble upon or make use of nature’s features in creative ways. We also used trees as interim anchors to secure ourselves in the event of an unexpected slip. Ensuring your system has redundancy is a paramount principle of climbing and rigging anchors.

Pitch 7: sketchy climbing

Just before the start of pitch 7 is a ledge that’s large enough to accommodate a stand of trees. Sheltered under their dappled shade, we took a longer break to hydrate, eat the rest of our snacks and celebrate having gotten through more than half of the route. There was a scary moment where my bag, unsecured and the recipient of Ryan’s accidental kick, tumbled in what felt like slow motion down the ledge but mercifully landed askew on a meager slant of grass covered rock. I scrambled down inelegantly to retrieve it but what the fuck, I was this close to losing my bag and all of our water.

Pitch 7 scared me. It was the most vertical section of the climb thus far, and from watching RZ, Ryan and E climb that pitch before me, I could tell that it was tricky even for them (and I think they are much better climbers than me). I knew that psyching myself out before a climb does nothing but intensify anxiety and make it more likely I would struggle, but the mind is an unwieldy creature and cruel master—it paid me no heed and continued to buzz anxiety at me like an annoying fly.

And so… I got a little lost climbing this pitch. My frustration mounted as the burning in my forearms—like sand in a time glass—steadily increased and I couldn’t puzzle out a sequence over the rock. I just didn’t know where to go. I was desperately searching, pulling myself up on tiny edges we call crimps, thinking this level of exertion didn’t feel right for the grade, when suddenly I felt that familiar stomach drop that accompanies being airborne. The rope is dynamic and therefore stretchy, so even though I was on top rope I fell quite a bit more than expected. “Whoa!” I cried out involuntarily and though I couldn’t see him, I heard Ryan’s concerned, “Everything ok?”

“Yeah, I just dry fired off a crimp. How did you do this section?”

Falling off on a climb is fine. Especially when this is your first time climbing it. But my shadow self couldn’t help but whisper at me “You could’ve finished this whole multipitch without a single fall” and I wanted that to be true. I wanted to be good enough to onsight every single pitch, just so I could say that if I didn’t fall even once, I technically could’ve climbed the whole thing without rope (obviously an illogical conclusion because climbing without rope is an entirely different mental challenge). How silly is the ego. How self aggrandising and delusional. How greedy it is for affirmation and importance, even when the situation clearly calls for a different focus.

Pitch 8: jungle climbing

There’s something darkly comical about trying to climb scrabbling on soil, pulling on tufts of grass, spindly shrubs and trees in a bid to go upwards on a massive tower of rock and thinking, “this is something the first ascensionists thought was fine to do.” It’s sketchy as fuck, it’s messy, ridiculous, and you feel absolutely absurd. I mean, the ground was literally crumbling away beneath my feet and there were more than a few moments when I was certain I would go tumbling down the dirt gulley. True to alpine style, it’s whatever goes, I guess.

Top out

Eventually, I stumbled out onto a lush plateau full of trees, soggy pitcher plants and dead leaves. Stepping over fallen logs, pushing aside branches and crunching through wet mulch led me to a large smooth hunk of rock that bulges out over the tower, giving us a 360 degree view of the island.

Et voila, the view at the top. What a privilege to see a view no one other than climbers get to enjoy.6

There’s even a bolt in the middle of this rock for you to clip into, so you don’t accidentally fall over the edge and hurtle 300m to the ground. So of course, as I neared the edge I began having intrusive thoughts like, “what if I tripped here?” “what if I sat too close to the edge and slipped?” “imagine if I pushed Ryan off” My brain is a fun place to be.

Rappelling on the descent

Yeah, we are only halfway through this adventure! Making it to the top is only the first part. Coming back down alive is the other.

It’s been a while since I’ve had to rappel to get down. Unlike Alpendurst, this tower has no hiking path down, owing to its verticality. The best way I can describe rappelling is that it kind of feels like what you see in those action movies where some elite military unit escapes a soon-to-explode building with ropes except a lot less smoothly and with way more trouble.

One annoying part about rappelling is aligning anchors to the direction in which you’re trying to come down. Often, the rope gets stuck somewhere and, apart from abrading the rope dangerously, you’re dead stuck hanging in midair because now there’s too much friction/force of pull is in the wrong direction.

Rope management is your eternal bugbear and coiling the rope at every anchor, making sure it’s free from knots and tangles and then holding your breath and praying as you yeet the rope outwards into the void never gets less terrifying. At each anchor you have to pull up the rope from the other end and manage all the equipment around the crowded bolts. It’s just a full on never ending physical and mental slog. With trees and shrubs peppering the tower, the chances of the rope catching on a branch or tree or over a sharp rock corner were high.

I remember almost losing my mind trying to rappel down pitch 5, slamming into this giant tree that was growing along a deep gulley. Every inch I tried to descend would have me swinging all the way to the left and getting caught in its branches, poking and stabbing me in all directions. Even when I managed to claw my way back onto the rock, the direction of pull would drag me away and off the rock and back into the tree. It was fucking exhausting and impossible. I felt genuinely stuck. There was nothing anyone could really do except try to encourage me. It’s confusing how alone you can feel even when you’re on that hunk of rock with other people. Rock climbing is very much a solo sport; our belayers and companions are merely passers-by on our mutual journey. Self-sufficiency is mandatory; independence a given.

The fuckery didn’t stop there. At the final rappel, we discovered that the area we were descending into was covered in moss and slimy algae. RZ called out a warning and I groaned internally. It was about 6pm and daylight was fading from the sky. I knew we’d have to hike back through the jungle in the dark. I’d been awake and exerting myself for 14h straight at this point. I wanted to just shut off my brain and go through the motions. But I couldn’t zone out, not just yet. Not until every one of us had gotten back to the entrance safely.

I was really grateful to Ryan for agreeing to take the position of last man. As juvenile as this sounds, I was afraid to be the last person coming down, being wholly responsible for rigging the rappel anchors and cleaning them and having no one behind you that could call out encouragement to you, or the person you say “going down now, see you in a bit” to. I had an irrational fear of being the sole person on the face, with only the lonely wind blowing through the landscape and the feeling that there wasn’t another soul in sight as far as the eye could see, or the mind could endure. If necessary, I would’ve absolutely done it, because there is no room for waffling or unreliability on these adventures; but as it turns out, Ryan is a better person than me, and apparently not as needy for human company 🤭

Past the limits of both body and mind, I was in that floaty, half-drunk state you get after a night shift or when you’ve been awake too long, as we traced our way back to our stuff and prepared for the trek back down through the jungle. I was past the point of exhaustion—supremely irritable—thinking the headlamps were too bright and the trek was taking far longer than I recalled it to be. Grumpy, tired, and hungry, I always find my worst self at the end of a long day out on a climb. Yet, to know that I am with companions who accept me for who I am in this moment, utterly free of pretenses—no ability to put them on, spent as we are—is a treasure few people encounter.

It’s like I said, somewhere between pitch 3 and 4’s anchor when all four of us were pressed up against the other, pulling rope in, arranging equipment, talking about how we couldn’t wait to enjoy a cold one with a big dinner later: “we are brothers and sisters now.” Irrevocably bound not by blood, but by rope and metal, sweat and fear, cooperation and sacrifice. A brief moment in a lifetime made up of a series of moments. Yet what is life but a collection of these joys and sorrows, some larger in your mind than others? When I look back, can I account for the moments: will I savour their recollection, or wonder how they’d gone by so fast? I can’t be sure. But moments like these, I know will accompany me forever.

Type III fun

In the planning stages, it doesn’t sound like fun. There are hazards to be mitigated. Hard conversations about risk to be had. The gear list dwindles to just the necessities, and comfort is always left behind. The execution confirms the hypothesis—this idea turned current predicament is indeed no fun […] Type III guarantees discomfort, fear, and a slow erosion of ego until the barriers between a person and the natural world become so thin as to almost vanish. Congratulations, you are now part of the ecosystem.

But a curious thing happens once the adventure is endured or survived. Shards of memories glow like embers, growing into a blaze that sustains profound feelings of gratitude, friendship or catharsis. It turns out the stars burn brightest at 3am. Difficult endeavors contain meaning. Who you are in the mountains is who you are. Type III fun has a way of revealing those truths.

— Fitz Cahall; Three Ways to Have Fun

Written by Shai-Ann Koh (MIR 22)

Originally posted on Shai-Ann’s Substack here

- https://www.patagonia.com/stories/sports/climbing/the-wall-as-a-mirror/story-148961.html

Read this excerpt from an expedition to climb Mirror Wall in the Arctic Circle: “We had 7 days of preparing the boat in Scotland, 16 days of sailing (most of which I spent vomiting), 5 days in the Faroe Islands waiting for a storm to pass, 14 days in Iceland waiting for the pack ice in Eastern Greenland to clear, 10 days of hiking back and forth carrying heavy loads over endless moraine and treacherous glacier, then 9 days of physically and mentally draining climbing, wrestling with loose rock, perilous skyhooks and massive runouts.” ↩︎ - A section of a rock climbing route with a long gap between points of protection ↩︎

- https://www.ukclimbing.com/logbook/crags/the_dragons_horns-22278/naga-496440#overview ↩︎

- Not Naga, but a more difficult multi pitch on South Tower is narrated by this wonderfully named blog. Read about another new route established a month after our climb here. ↩︎

- A specialized training tool designed for rock climbers to build specific finger strength, forearm endurance, and shoulder stability. It is a wooden or plastic board featuring various holds—such as edges, pockets, slopes, and jugs—mounted on or hung from a wall to allow for dead-hanging, which isolates the finger muscles. ↩︎

- There are no hikes that take you to the summit of either tower. The other tower has a hiking path and a very short via ferrata segment, but it still doesn’t go all the way to the top. ↩︎

Leave a Reply